Sparkle feature: Bejewelled treasures throw light on India’s exquisite past and present

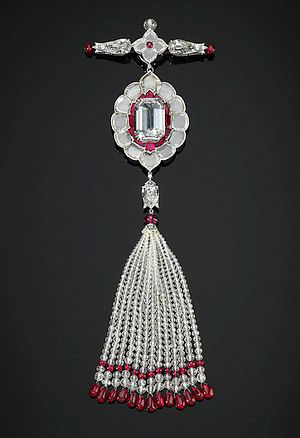

Brooch, designed by French designer Paul Iribe and made by Robert Linzeler. Paris, France, 1910. Credit: Servette Overseas Limited 2014.

Photograph: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd.

One of the most extensive collections of Indian jeweled arts is held by a member of the Qatari royal family. Spanning more than four centuries, these opulent riches are now on display at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, and are joined by three jewels owned by the Queen of England.

A new exhibition at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum now shows off some of the most spectacular Indian and India-inspired jewels and jade. From diamond turban ornaments to silk sword sashes with jeweled fittings—and even a jewel encrusted back scratcher—approximately 100 pieces are currently on display, thanks to a loan from Qatar’s Sheikh Hamad Bin Abdullah Al Thani, first cousin to the current Emir of Qatar.

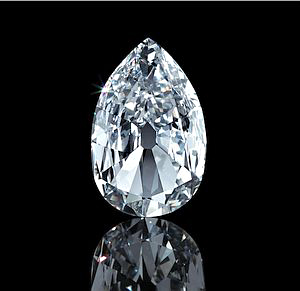

Spanning four centuries, the objects in Bejewelled Treasures tell stories of love, power, war, and politics. Included are extraordinary diamonds and gems, such as the Arcot II Diamond, given to Britain’s Queen Charlotte in 1767 by the Nawab of Arcot in South India. The Nawab, or governor, had a close relationship with King George and Queen Charlotte, and wrote to them often. He gifted the 23.65 carat diamond to the Queen after it was unearthed from the famed Golconda diamond mine in southern India.

Collecting: An Al Thani family pastime

Sheikh Hamad, 33, has amassed this extensive collection over the past six years.

“Growing up I always had an aesthetic eye and I was drawn to three-dimensional objects,” he said recently. “However, it was not until late 2009 that I started collecting jeweled arts from Mughal India. A turning point was the Maharajahs exhibition staged by the V&A in that year. Since then the collection has grown in leaps and bounds.”

Collecting art has become something of an Al Thani family pastime. Qatar’s first family includes some of the world’s most voracious buyers of art. In 2011, the Qatari royals acquired Cézanne’s The Card Players for a record-breaking $250 million. It has also been rumored that the Al Thanis were behind the purchase of Edvard Munch’s, The Scream, which sold for $120 million last year.

Last year, Sheikh Hamad exhibited around 60 of his Indian treasures in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Still, London has a special significance to him as the city where he spends much of his time. The press-shy sheikh lives in Dudley House, a palatial residence in the heart of the capital, which he acquired nearly 10 years ago and spent years renovating.

His 17-bedroom house, complete with ballroom, prompted the Queen of England to remark that it “makes Buckingham Palace look rather dull,” according to Vanity Fair.

It is thanks to the sheikh’s personal friendship with the Queen that she lent three objects from the Royal Collection to be included in the exhibition. They include the so-called Timur ruby and a jewel-encrusted backscratcher. In fact, the Timur ruby is a misleading name since it was never owned by Timur, the 14th century conqueror of central Asia—nor is it a ruby. It is a 352-carat spinel, a red stone found in Badakhshan, which curator of the exhibition Susan Stronge has said was “valued above any other precious stone at the Mughal court.”

Meanwhile, the 1.2-metre-long, 18th-century backscratcher, probably owned by Robert Clive of India, is crafted from nephrite jade with a tiny ruby and emerald set in gold.

Anita Delgado’s peacock brooch by Mellerio dits Meller. Paris, France c. 1905. Credit: Servette Overseas Limited 2014. Photograph: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd.

Stories behind the jewels

While Sheikh Hamad is involved in the selection of each piece in his collection, his favorite is a jade dagger which belonged to two emperors. Originally made for Indian Emperor Jahangir in the early 17th century, it was passed down to his son Shah Jahan, who built the Taj Mahal.

Other pieces in the exhibition tell stories of love and romance. That’s certainly the case for one of the most captivating ornaments – a gold, diamond and enamel peacock brooch. Designed by Mellerio dits Meller in Paris, it was purchased by the ruling maharajah of Kapurthala in the Indian state of Punjab, Jagatjit Singh, in 1905. Just after buying the piece, he travelled to Spain, where he fell in love with 16-year-old dancer Anita Delgado. He took her back to Paris, where he made her his fifth wife and gave her the brooch, which she wore in her hair in a portrait in 1907.

The peacock was just one jewel that Delgado received from the maharajah. After noticing a crescent-shaped emerald on one of the royal elephants, she asked if it could be hers. He promised she could have it if she learned to speak Urdu, and then gave it to her on her 19th birthday. She wore it as a bracelet, necklace, and hair ornament.

Many objects in the exhibition highlight the influence that India’s design motifs and gems have had on designers far beyond its shores.

In 1910, Paul Iribe, French illustrator, designer, and Coco Chanel’s lover, used a carved Mughal emerald as the centerpiece in one of his early brooches. The shape is reminiscent of a turban, and the mix of the emerald with sapphires, diamonds, and pearls was unique for the time.

Even today, classic Indian motifs resonate with designers. Renowned Parisian jewelry designer Joel Rosenthal drew on classical Mughal architecture to design an emerald brooch surrounded by diamonds and rubies in 2002. Similarly, Mumbai-based Viren Bhagat uses Mughal forms in his work. His striking platinum brooch, designed in 2011, features a mix of diamonds and rubies.

“This is a fascinating insight into a great private collection that includes extraordinary precious stones, both unmounted and set into jewels,” said Martin Roth, Director of the V&A. “The exquisite quality and craftsmanship of many fine pieces from and inspired by India complement the V&A’s own South Asian and jewelry collections and will be a spectacular element of the Museum-wide India Festival this autumn.”

Huma bird from the canopy of Tipu Sultan’s throne. Mysore c. 1787 – 93. The Royal Collection Trust. Credit: Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2015.

Bejewelled Treasures: The Al Thani Collection, Victoria & Albert Museum, London (until 28 March 2016)